I do not like films that focus on gore. There are many kinds of films I do not care for at all, but for which I can at least appreciate why people find them appealing:

Transformers/Marvel-esq fantastical blockbusters can be fast-paced and dazzling,

Romantic comedies can be cute and heartwarming,

Pixar animated features can be VERY cute as well as funny and captivating to children,

but horror movies that focus on the threat of slow disembowelment of still-living victims and that tease (via previews) said disembowelment will be in the center of the frame for much of the film’s running time, well, I just can’t understand why anyone wants to watch that.

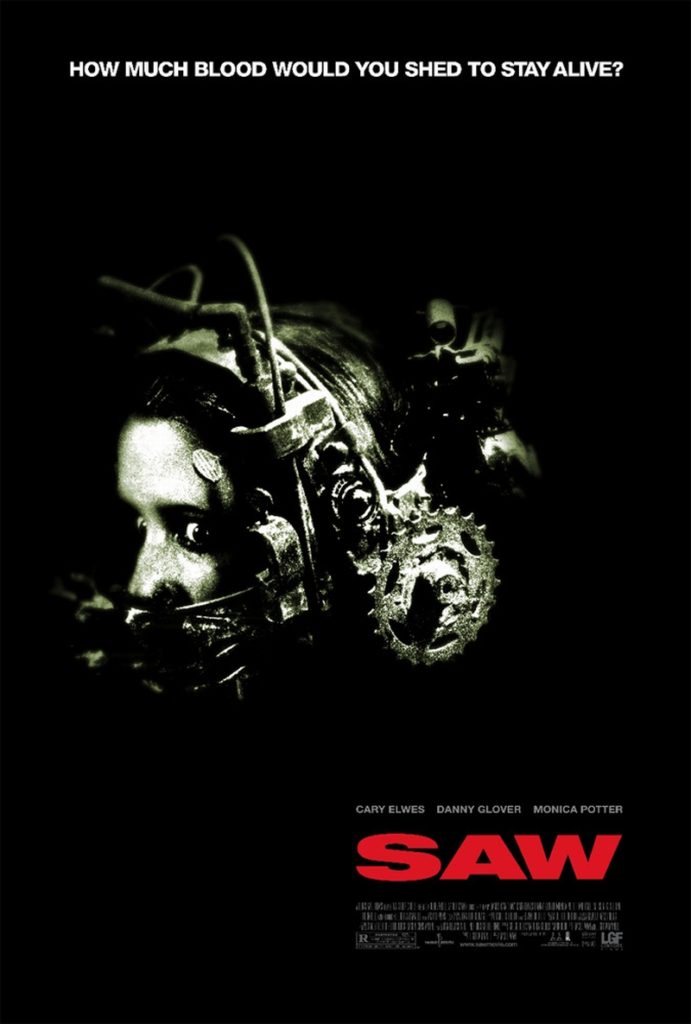

The most recent trend of highly gore-focused horror movies or “torture-porn” really got going with Saw in 2004. Though it seems to have lessened in popularity the past few years, many of the films that were part of it were very successful at the box office and gained cult followings. I’m not turned off by movies featuring so much gore because they are scary but because they’re simply disgusting. Disgust and fear can and often do overlap, but I like a film or piece of literature that makes me a bit or very uneasy without turning my stomach and putting an unwelcome image in my head that I’ll have a hard time getting rid of.

It’s not hard to see why Hollywood turned toward gore as a selling point for movies. Gore creates disgust which is a strong reaction and practical effects have advanced to make for some uncanny viscera to come out of victims at the hands of villains. Jump-scares have increased in popularity for the same reason, they get a reaction, a reaction that is even easier to get than disgust.

If individual audience members have a strong reaction to a film, be it good or bad, it’s more likely to become popular and make more money than a film that gets fewer strong reactions from anyone and is widely regarded as “meh” or boring.

Jump-scares create a startle response, but that doesn’t necessarily equate to fear that will linger with the audience for more than a few minutes, let alone after the movie is finished. Many horror films today feature both disgust and jump scares, elements designed to get a reaction, neither of which requires as much talent as the ability to write a good, scary story that makes someone hesitant to enter a dark, silent, empty house in the countryside or go to sleep for fear of nightmares.

I do like some horrific stories, but they are not all categorized as “horror”, I like stories that disturb the audience with more sophistication than those that rely on gore and jump scares, my favorite kind of horror is what I call intelligently disturbing. Intelligent because it takes some intelligence to both tell and absorb such a story. Such stories cannot simply be cranked out, nor is the horror element they contain always especially obvious. The best sort of horror is the kind that lingers and gets under your skin. Such an effect of “sinking in” doesn’t happen immediately, it takes time, it takes patience on the part of the audience as well as the storyteller.

The first story that I realized was intelligently disturbing was Children of Men. Though not a horror movie, it is a story of desperation in the face of hopelessness. The film (based on a novel of the same title) takes place in the near future where a massive epidemic of infertility has caused no human child to have been born in 18 years. The protagonist, Theo, is recruited by an ex-girlfriend to escort the world’s only known pregnant woman to a secret community of scientists before a nefarious government and other factions discover her. The cinematography, performances, and score all combine to convey a tone of raw brutality that stuck with me since my first viewing. The film (and book it was based on) are often categorized as “dystopian” but I don’t think that’s accurate.

My thoughts on the “dystopia” label are enough for another whole article but compared to many other science fiction films categorized as “dystopian” in the past couple decades, the problems that are the result of an oppressive government are minimal. The feeling of dread that the movie so skillfully conveys is the result of this epidemic of infertility whose cause is unknown, not some rigid, stifling social order or cartoonishly evil ruling class as in so many of the dystopian films of late, adapted from young adult novels.

The world of Children of Men is gripped with despair because there is literally no future because there will be no more children. This is far more chilling to me than one where the aristocracy forces twelve of the peasants’ children into a battle royale once a year. This is also more unsettling than a plot involving unwitting people getting captured by a sadistic killer.

When I was attending university, I took a course in the history of cinema and one day after class, mentioned to my professor why I liked Children of Men for this rather disturbing aspect that bore so little resemblance to much of contemporary horror, and yet, was rather horrific. He seemed to understand what I was getting at and said that another, somewhat similar example to that would be Funny Games by Michael Hanneke.

Funny Games (1997) is an Austrian film (there was an English language remake of the same title by the same director in 2007) about a wealthy family, consisting of a married couple and their ten-year-old son, who goes to their country home for the weekend. Once they arrive at their country home in the evening, they are held captive by a pair of psychopaths who bet that the family will not survive until 9 am the next morning. There is some violence but it’s less graphic than anything you’d see in a James Bond type action thriller. The horror comes not from physical harm itself but the constant threat of harm from the psychopaths toward the family.

The most uncomfortable scene for me to endure, by a longshot, is early on before the more intense action begins and involves no violence at all. One member of the duo that will go on to torment the family shows up at their door to borrow some eggs and keeps “accidentally” dropping them before he’s even out of the kitchen and then asking for more. By the time this happens twice the mother is exasperated and the tension is almost palpable. This sets the tone for the creeping sense of brutal dread that gives the film its impact.

The titular Funny Games played by the villains upon the family amount to psychological torment. This takes place at a country house in 1997 where the phone has been disabled so this seems more plausible. The film brilliantly conveys the villains’ playful sadism and the victim family’s feelings of helplessness in the face of a foe that is not supernatural but simply evil, without mercy. Bloody torment is only threatened for the briefest of moments, the main threat is a quick death, but the mundane-ness of the situation combined with the unflinching style of the cinematography and edit, combined with a lack of any music makes those looming deaths carry more weight. The way the villains operate is deeply chilling without involving elaborate schemes or magic ability.

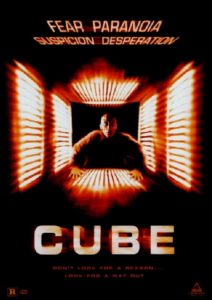

One film that is actually categorized as horror, science fiction horror specifically, that I find to be intelligently disturbing is Cube. Some may point out that Cube is highly derivative for drawing upon the horror trope of a bunch of strangers waking up in a hostile environment and getting picked off one by one. While this is true, the twist of this trope comes in the form of the hostile environment.

Instead of a haunted mansion, the characters find themselves in a cube where each cube-shaped room has portals in each of the walls, the ceiling, and the floor, that lead to other identical, cube-shaped rooms, many of which contain deadly traps. In order to survive, they must find a passage out of the greater cube, which consists of 17,576 such rooms (26 x 26 x 26), via passage through rooms that are safe.

Unlike a film such as Saw where drugged victims wake up already bound inside traps inside dingy rooms, or even a horror classic like Alien where passengers are trapped aboard a poorly lit spaceship with a highly hostile extraterrestrial, Cube features an environment that seems sterile and neutral to the point of boredom. The trap-containing rooms of the Saw films would look dirty and even scary without containing any bound victims or torture devices. The rooms of the Cube, had the film never been made, the film’s setting might look like the set of a music video of some electronic music act from the 1990’s.

The impact of Cube comes from the characters being in such a sterile environment and was actually inspired by an Episode of the Twilight Zone “Five Characters in Search of an Exit” which was inspired by the existentialist stage plays No Exit and Five Characters in Search of an Ending. The scenario in Cube is less scary insomuch as invoking feelings of fear and disgust like a haunted house or an abandoned hospital but more absurd like characters in an existentialist play where there is nowhere to go and nothing to do.

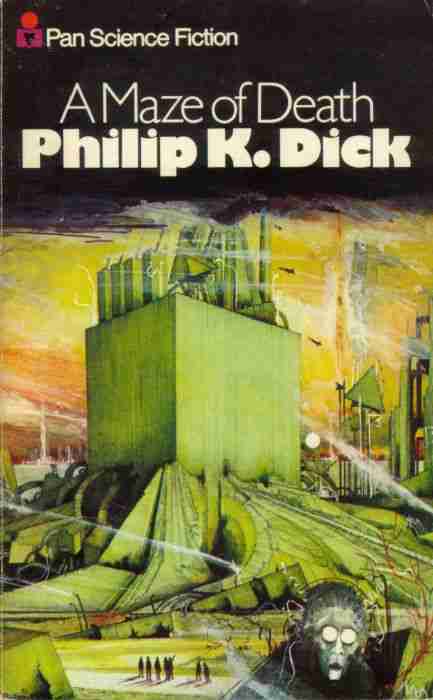

Characters being trapped not with a killer or monster but merely with one another and not in a murderously paranoid “The Monsters are Due on Maple Street” (an episode of the Twilight Zone) sort of way but with rather mundane, irritable boredom is the scenario of a great intelligently disturbing science fiction genre novella by Phillip K Dick titled A Maze of Death. A Maze of Death’s plot involves a group of randomly selected people from around the galaxy sent to colonize a newly settled planet. Though they all did volunteer to be sent to a new colony, several of them did so merely because they did not like their former jobs on other colonies or aboard interstellar spaceships.

The inhabitants of the new colony on Delmak-O are soon faced with a mystery as one of them has been murdered. When they try and contact the appropriate authorities, a sort of interstellar command, their means of communication beyond the planet are severed. The colonists’ situation quickly becomes more and more intense as well as bizarre with one twist after another. There is no monster, secret killer, physical torment, or even threat of torment, but there is a dread of wondering what is going on and if the characters will ever find out and have some sort of explanation for the chaos they’ve found themselves in.

What stuck with me about A Maze of Death was how quickly the characters were all sick of one another, like a dysfunctional family stuck on a desert island. A group of people who all hate each other, stranded on a planetary colony with plenty of provisions (starvation is no threat) but no means of escape or contact with the outside world, gets under my skin with creeping horror far more effectively than a pair of rubes who wake up trapped in a room together, ostensibly having to mutilate themselves or each other in order to escape.

A classic short story of the horror genre that gave me the creeps without so much as a paper cut is The Willows by Algernon Blackwood. It was published in 1907 and features a pair of men on a canoe trip down the Danube through Romania around that time. Far away from civilization, they make camp for the night on an island hear some very strange sounds and find in the morning that one of their paddles is missing and the canoe has been damaged.

That day, while they repair the canoe and make a new makeshift paddle, they also find very strange tracks in the sand and realize that creatures are stalking them, creatures that sense them most keenly when their minds are active while they are awake, so they must sleep until the morning to survive. The Willows was an enormously influential work and the personal favorite short story of none other than HP Lovecraft. Its scare factor comes from the very strange, the deeply unfamiliar with very little in the way of violence. What scared me about The Willows is the threat of the deeply strange, the supernatural and unfamiliar in the wilderness. Death at the hands of things are not well understood or even known is most unsettling.

Perhaps the most chilling book I’ve ever read that did much to scare with little violence was the post-apocalyptic novel The Road by Cormac McCarthy. Those who’ve read the book will be quick to point out that there are indeed a few scenes of violence, gore, and the threat of both, but those instances take up just a few pages from the whole book. Readers who need a great deal of action to stay interested would be bored. The Road isn’t just another zombie apocalypse or Mad Max type situation.

A nuclear apocalypse type catastrophe (the novel never states the cause of the all the destruction) has plunged the world into an endless winter where the sun shines dimly through a thick overcast and temperatures never rise above the 30’s on even the warmest of days in the Southeastern United States. Taking place around ten years after the catastrophe, all plant and animal life (save for humans) appears to be dead. The only other living things are humans, almost all of whom are extremely hostile.

Though they are completely “free” and not stuck inside a structure or on an island, there is little to no signs of life anywhere and no food and hardly any resources such as oil for a lamp or dry warm clothes. I first read the Road in the wintertime and reading it at night gave me such a sense of fear and dread that I was a little afraid the sun might not come up the next morning. The disturbing factor of the story came from the sheer desolation, a world without hope to make any Mad Max or The Walking Dead look like Disneyland.

In my view, for a story to be truly scary, it needs to move the audience out of its comfort zone with some substantial depth of feeling. This is done best by taking something that we would usually take for granted as mundane and giving it an unfamiliar quality. This is what intelligently disturbing fiction does best.