Sergei Eisenstein made his later films in the Soviet Union while Joseph Stalin was in power. Artists working in the Soviet Union at that time were embattled by censorship. Anyone even remotely suspected of sedition could be incarcerated if not executed. Citizens had to use discretion with what they said and filmmakers like Eisenstein needed to use great caution with what sentiments were expressed in his films. The only art style of that period that was officially endorsed by the government was socialist realism. In A Short History of The Movies, Mast and Kawin define socialist realism as “The Stalinist insistence that art serve the interests of the state and be clear to anyone; to be artsy was to be elitist and confusing, and to deviate from the Party line was to fail to communicate plain reality.”

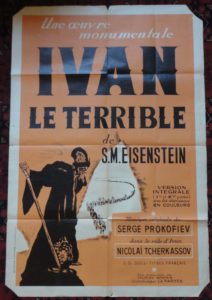

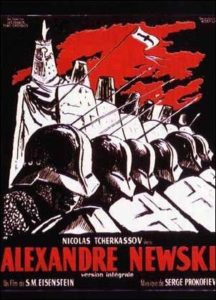

In order to make major films in his home country, Eisenstein had to portray the Russian proletariat in a very positive way and all of Russia’s enemies, past and present, in a very negative way. The films Alexander Nevsky (1938) and Ivan the Terrible Part Two (1958) are stories of the Russian people supporting great leaders in order to overcome their enemies. The characters Nevsky and Ivan are portrayed as popular champions of the common people in their respective films not just through actions and dialog but they are clearly shown to be through the use of mise-en-scene. In both films mise-en-scene, particularly the placement of actors and decor to emphasize the contrast between the proletariat culture of Russia (in both films, taking place centuries before the concept of communism existed) and the elitist, despotic culture of its enemies.

Alexander Nevsky is the story of the titular hero who was a real-life thirteenth century Russian Prince who succeeded in defending Russia from invading German Knights. Nevsky first appears standing in knee-deep water in a lake with several of his subjects (dressed in simple white tunics just like his own) standing in the water as well, holding fishing nets, stretching out into the distance behind him. He is already known as a popular leader from the start of the story and this is illustrated by a long line of his people standing behind him in the background literally backing him up. Despite his status as a prince, Nevsky works alongside the peasants, as another mere fisherman. In sharp contrast to Nevsky’s egalitarianism is the Governor of a passing Mongols Horde who offers for Nevsky to join them as a captain.

The governor rides in an enclosed litter carried by four soldiers. When he steps out and later steps back in, another soldier lays down on his belly in front of the door to the litter so that the governor can use his back as a step. As the two men converse the Mongol Governor appears chubby and stands about a head shorter than Nevsky in the left side of the frame, grinning, stroking his beard and making small gestures with his right hand. Nevsky stands proudly on the right side of the frame with his hands on his hips and his chest lifted. Not only is the Mongol Governor portrayed as menacing and decadent, he is a physically smaller man than Nevsky (once the two share the same frame) in spite of his greater political and military power. Though the Mongols were among Russia’s enemies at the time the film takes place, Germans were Russia’s greatest foes both in the story of the film and at the time of the film’s production and release. Alexander Nevsky was released in Russia in 1938 at a time of great political tension between anti-communist Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. The portrayal of the thirteenth century Germans as cruel aggressors coincided perfectly with the current hostility between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. In the online magazine Senses of Cinema, Greg Dolgopolov writes

The film was designed to mobilize and bring confidence to the worldwide struggle against fascism. Throughout the 1930s, relations between the USSR and Germany were in a constant state of flux. Germany’s rearmament, Hitler’s avowed anti-communism and the weakness of the European policy of appeasement were cause for enormous anxiety.

The Germans first appear in Alexander Nevsky as they have just succeeded in sacking the Russian City of Pskov. The scene begins with a shot of four German knights in full armor, including helmets that completely conceal their faces, standing in a row in front of a large arched portal. They are all holding spears topped with banners flapping in the wind. In the bottom left corner of the frame, the corpse of a Russian peasant man lies face down on the ground. The following shot zooms out to reveal another four knights standing in a row atop the wall that the archway is a part of as well as smoke billowing from an off-camera fire. The next shot zooms out even farther to reveal partially burned wooden structures on fire as the source of the smoke as well as more knights standing along the city walls. A few additional knights stand along the city streets with their backs, (covered by white capes emblazed with the cross) facing the camera. The city streets are littered with corpses of slain Russian peasants. A dead horse lies in the street at the bottom center of the frame. Though they have not been shown taking any action yet in the film, the viewer knows it is the German Knights, faceless behind their visors that are responsible for this scene filled with destruction and carnage.

A later shot shows the noblemen of Pskov tied up and on their knees with their backs to the camera in the foreground and in the background, the German Archbishop is seated on a throne at the top of some stairs. He is immediately surrounded by princes, standing in full armor and farther out by wide rows of knights and soldiers, all of whom are situated clearly above the noblemen of Pskov in the frame. Soon after, a medium shot shows one of the German princes speaking. Though he has removed his helmet to reveal shoulder length straight blonde hair and a clean-shaven face, in the top left corner of the frame there is some sort of grotesque four-legged demon or gargoyle that is carved into the wall behind him. The same creature appears in the same spot in the frame in a medium shot of the Archbishop when he rises to speak a few minutes later.

In spite of their arrogance and strong belief in their own superiority, the German leaders are compared to ugly monsters within the context of the frame. After some speeches by the Archbishop and the princes, in a shot facing the bound noblemen of Pskov, still on their knees (in front of the Archbishop and princes as established by a previous shot) when one of them rises to his feet to speak against the German leaders. When he rises, his head is not only above the standard-cross held aloft by a monk in the middle ground but also higher than the banner-topped spears of the knights who line the wall in the background.

Foot soldiers are ordered to seize the offending nobleman and the rest of the noblemen for execution. As the foot soldiers run into the shot they come only up to the height of his shoulders (perhaps because they are crouched in order get a better hold of him) and appear impish and menacing in their helmets that cover their faces above their mouths. As before with the Mongol Governor, when placed in the same frame (presumably standing on level ground) the Russian leaders appear taller and more honorable than their enemies, showing their true superiority. The nobleman is then lifted by ropes and hung from the side of a tower. As his whole body hangs in the center of the frame, an angel (about the same size in the frame as the nobleman) is carved into the wall of the tower behind him to the left and thick black smoke filling the frame in front of him to the right. Though the film casts religion, specifically Catholicism in a very negative light, by visually comparing the nobleman of Pskov to an angel, Eisenstein makes it clear that the man is a saint of his people, or at least, a martyr. In socialist realist narratives, if heroes sacrifice themselves, it is always for the good of the masses. The burden of loyalty to one’s people is a subject Eisenstein thoroughly explores in Ivan the Terrible Part Two.

Ivan the Terrible Part Two begins with a brief recap of the events of part one which ended with Ivan abdicating the throne and leaving Moscow for the monastery of Alexandrov to the north. Upon his abdication masses of peasants followed Ivan to Alexandrov to beg him to return to the throne. This is shown in a shot of a winding road filled with peasants walking toward the camera (toward Alexandrov) that stretches all the way to the horizon. The next shot zooms out to include a close up of Ivan’s facial profile in the right half of the frame as he looks down paternally with a somber expression from some high vantage point. In the next shot, Ivan stands on the left side of the frame, wisely gazing into the distance in his ankle-length black fur coat with his right hand atop his scepter/walking stick. Taking up the center of the frame immediately to his right his young aide stands smiling (as Ivan has just informed him of his plans to return to Moscow to reclaim the throne) and on the right side of the frame an open archway reveals the long procession of Ivan’s adoring supporters, winding off into the distance. Here, as in Alexander Nevsky, the popular leader is shown “backed up” by his people not only figuratively but also literally.

The first scene featuring the court of the Polish King, Sigismund III stands out in its contrast to all previous scenes that have featured the one other monarch of the film, Ivan. In it, Ivan’s trusted friend, who was sent to defend the eastern border from Poland, has betrayed Ivan and come to the Polish King to defect. The first shot is taken from a high angle and reveals the court to be ornate, yet sparsely populated for such a large space, especially compared to the previous scene of Ivan showing the masses following him. The floor of the court is made up of black and white tiles like a giant chessboard. In the bottom left corner of the frame, farthest in front of the throne, the captains of the guard stand in shining armor with their massively plumed helmets held under their arms before a tall statue of a classical warrior. Farther back, just to the left of the throne, some religious officials stand in fine robes. In the right side of the frame, in the middle distance from the throne between the guards and the theologians, the queen stands with several noblewomen and attendants. At the top center of the frame, the king sits slouching to the left on his throne with two ornately dressed servants to the right.

On the wall behind Sigismund is a giant mural of two knights jousting. A later shot zooms in closer and the king is seen wearing a feathered hat, a ruffled collar that reaches out to his shoulders, a large earring on his right ear, a many-jeweled necklace, a waistcoat-like tunic, tights and fur shoes. Though he sits beneath an image conveying bravery and honor (the mural of the joust) the king himself appears obsessed with finery, pomp, and ceremony. He does not even sit on his throne with dignified posture but slouches like a bored spectator. Powerful and wealthy, yet paradoxically superficial and impotent, the King of Poland looks like a foppish fool. He is not a menacing, powerful threat like the Germans in Alexander Nevsky, but he represents the inferiority of Polish culture that was found to be arrogant and aloof compared to that of Russia both in the time the film takes place and the time the film was made.

Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible Part Two were made in a time and place where films had to show clear support for the ruling government. They both used stories of great leaders of the past and portrayed them as champions of the people in contrast to the leadership of cruel and decadent enemies. This was done not only through narrative and dialog but also with the clever usage of mise-en-scene with décor and character placement. In spite of tremendous pressure to make films that had to convey specific messages to do with the current political climate, Eisenstein was able to employ several visual elements to help tell the story is a finer, less direct manner than words or overt actions. His usage of mise-en-scene to tie together plot, characters and action is a large part of the reason these films are widely considered classics and Eisenstein to be a master.